EXPLORING OVERLAND

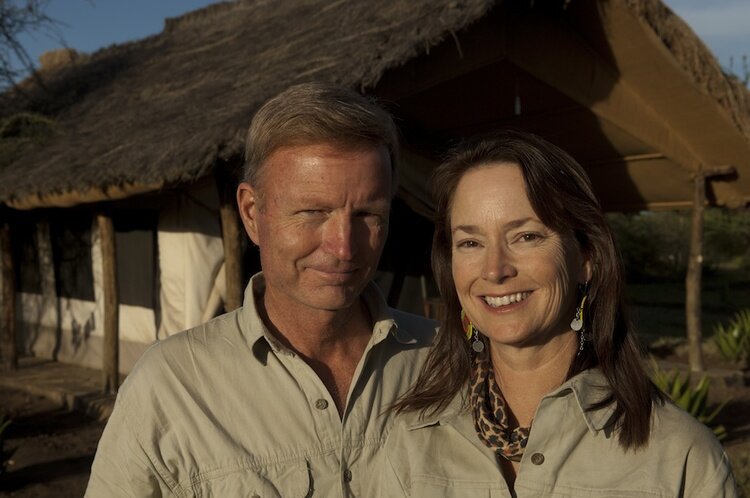

JOIN OVERLAND EXPO FOUNDERS ROSEANN AND JONATHAN HANSON EXPLORING OVERLAND, WHETHER IT’S CLOSE TO HOME OR ACROSS THE GLOBE, THROUGH WORDS, IMAGES AND FIELD ARTS.

FOLLOW ROSEANN @ROSEANNHANSON

FOLLOW JONATHAN: OVERLAND TECH & TRAVEL

We remember the first time a fellow walked up to us in a dispersed BLM campground, pointed at the large folded contraption Jonathan had just uncovered on the roof rack of his Land Cruiser, and asked, “What’s that?”

“It’s a roof tent,” Jonathan replied, combining two nouns he had clearly never heard in the same sentence.

“So you carry it up there?”

“No, it stays there. Watch.” Jonathan pulled a cord and the Technitop blossomed open in all its canvas glory.

He looked at it, open-mouthed, walked all around it as Roseann hooked up the ladder.

“So you sleep up there.”

“Yep. Very comfortable. And it can’t blow away.”

He walked away back toward his camper, shaking his head. “I’ll be damned. A tent on a roof.”

How different things were just 13 years ago, when that incident occurred. Back then few people in the U.S. had heard of or seen a roof tent—or a portable 12V fridge that could keep ice cream frozen, or a camping trailer that could follow a four-wheel-drive vehicle down the roughest of trails.

In fact—this has been verified by historians—in 2007 very few Americans were even aware of the existence of a company called Snow Peak.

Image credit: Roseann Hanson

It’s not like we didn’t camp. Americans had a long and cherished tradition of heading out for the weekend to a national park, national forest, or BLM land and enjoying a few nights under clear skies and sharp stars, fishing, birding, canoeing, or just relaxing in our webbed aluminum beach chairs. But the tradition was generally more of an out-and-back activity—you went somewhere and camped, then you went home. And, with few exceptions, car camping equipment here had strayed little from a formula followed for decades: You either had a camper mounted on a pickup truck, or you had a canvas or nylon tent and cots. If you wanted cold food and drinks, you brought along an ice chest. You cooked on a pump-pressured white gas Coleman stove or, later, its propane equivalent.

This newfangled—at least to us—thing called “overlanding” was different. For overlanders, the journey itself was the goal, not any particular destination. It was about exploring new country, being completely self-sufficient. When possible, organized campsites were spurned in favor of more remote, pristine vistas. While a weekend trip might qualify perfectly as overlanding, there was also the potential to extend that weekend into two weeks, six weeks—or six months or six years. And the equipment available from sources in South Africa and Australia was designed to turn a four-wheel-drive vehicle into a comfortable home away from home suitable for extended exploration. “Overlanding” was the right conceptual tweak at the right time to a well-established pastime, and it took off.

Humans have traveled and camped for millennia, from the first migration out of Africa into Asia and Europe, to later ventures across the Bering Strait and through the Americas, right up to the westward expansion of Europeans across the North American continent.

Pearce Arrow

But it wasn’t until the early 20th century that we started doing it for fun. And it was the internal-combustion engine that made that possible (few people would have called overlanding by covered wagon and a two-brace draft of oxen fun). Pierce Arrow debuted the Touring Landau in 1910, with a rear seat that converted to a bed, a fold-down sink, and a chamber pot. Henry Ford’s Model T hadn’t been on the road for long when enterprising craftsmen began constructing elaborate motorhome bodies on them. By 1923 you could buy a kit from the Zagelmeyer Auto Camp Company that would convert your Model T into a pop-top camper with fold-down side beds—the top lifted automatically as you folded down the sides. Shortly thereafter another iconic invention appeared, one that would be critical to future outdoor activities: In 1927 the Girl Scout manual published the first official recipes for S’mores.

Land Cruiser on Safari in Kenya. | Jonathan Hanson

About this time, African safaris began to evolve from foot to motorized. The same year the Girl Scouts were touting their S’mores, the first three cars visited South Africa’s Kruger National Park. The year after saw 180, and those numbers grew rapidly. Meanwhile, a wayside stop on a track in Kenya originally known simply as Mile 326 grew to become the center of a huge safari industry, and adopted the formal name Nairobi.

A sea change took place after WWII, partially due to the introduction of civilianized Jeeps, the Land Rover, and, a bit later, the Land Cruiser, along with other affordable four-wheel-drive vehicles, and partially due to a burgeoning economy. The 1950s and 1960s in the U.S. witnessed an explosion of outdoor recreation. In 1953 Don Hall introduced the Alaskan Camper, with rigid walls and a lifting roof, reportedly fashioned after a hat box his wife showed him in camp one night after their truck almost overturned. In 1972 Dave Rowe lightened the concept considerably with soft sides, and produced the Four Wheel Camper. These seminal products pioneered the idea of a comfortable camper that only minimally reduced the capability of the truck on which it was mounted to access remote backcountry destinations, while providing a weatherproof, self-contained shelter.

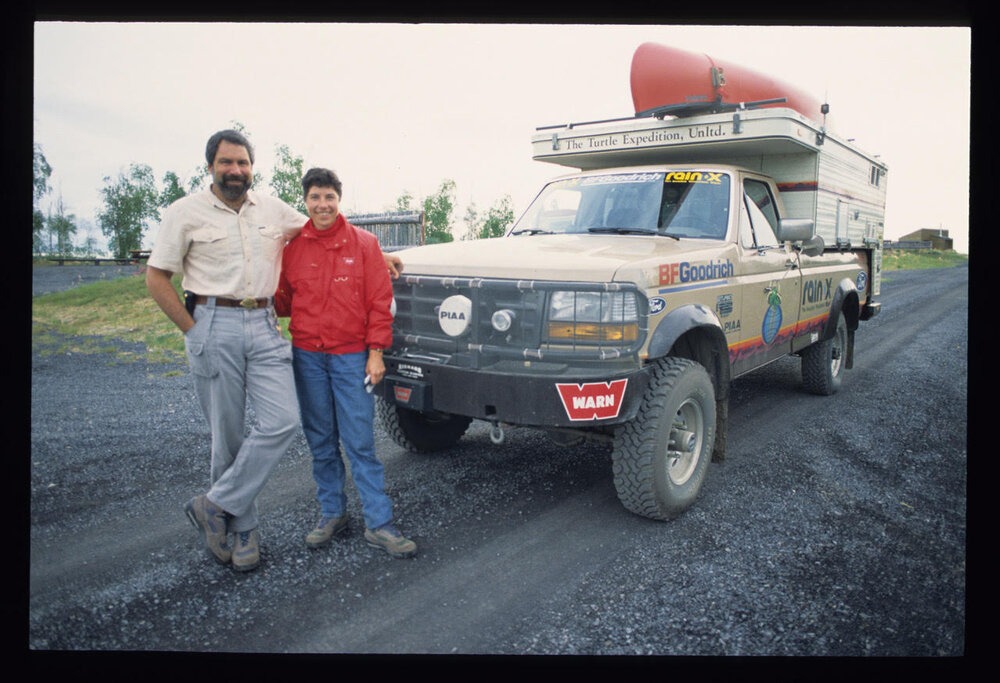

Gary and Monika.

In the mid-1970s Jonathan began following the exploits of a couple named Gary and Monika Wescott, who traveled full-time in a highly modified Series II Land Rover 109. Through the succeeding decades—and succeeding pickup trucks starting with a (suspiciously short-lived) Chevrolet followed by several Fords mounted with Four Wheel Campers—the Wescotts introduced the concept of long-term overlanding to me and other readers dissatisfied with the dominant paradigm of weekend “wheeling.” In 1984 Jonathan stumbled on an article in the British magazine Car by a chap named Tom Sheppard, who had led the first west-to-east traverse of the Sahara Desert, and who now specialized in off-tracks journeys in its most remote areas. Jonathan had found a new hero.

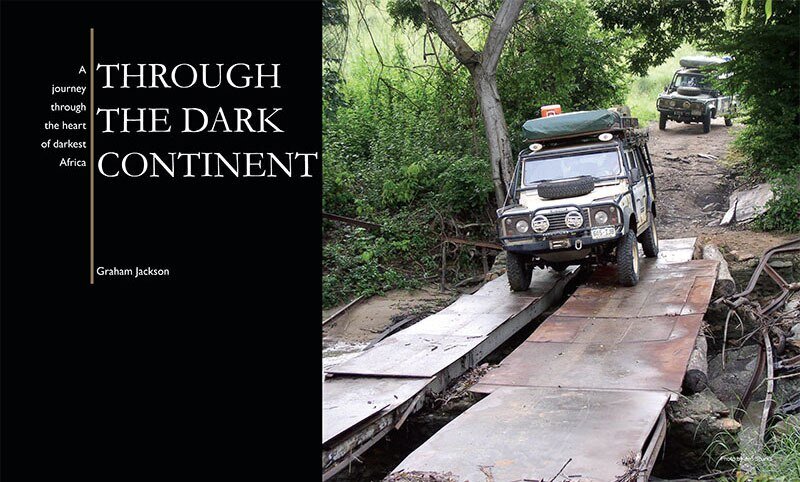

Graham Jackson’s story in Overland Journal.

Fast forward 20 years. We had writing careers of our own and, with both a Land Cruiser and a Toyota Tacoma/Four Wheel Camper in our driveway, we were committed disciples of traveling so “the journey itself is the goal.” Thus it made sense to combine the two, and in 2007 I became the founding editor of a new magazine called Overland Journal. There was nothing else remotely like it on this continent, but despite (or because of) that, growth in subscriptions was slow at first, so Roseann came up with the idea of a combination trade show and instructional gathering called, logically enough, the Overland Expo. The first one was held in Prescott, attracted 900 people and some very brave vendors.

Simon and Lisa.

And the rest, really, is history. This new/old concept caught on in a huge way with thousands of people who owned or wanted to own four-wheel-drive vehicles or adventure motorcycles but had little interest in just looking for tougher trails every weekend. As the word spread, we heard from more and more readers and attendees who were inspired to expand their worlds through travel, even if they were still limited to two weeks per year. And more than a few were captivated enough by the stories of fellow travelers, and of pioneers such as the Wescotts, Tom Sheppard, Ted Simon, Lois Pryce, Elspeth Huxley, and others, to drastically alter their circumstances and make travel the centerpiece of their lives.

Photo credit: Chris Collard

In 2011 it became clear Jonathan needed to move on from Overland Journal, and just last year it became clear that the Overland Expo had become too big for Roseann to manage if she still planned to do any traveling herself. But the momentum is unstoppable now. In fact, you know a concept has arrived when people start rolling their eyes at the overuse of the term, and its application to things totally inapplicable. It happened in the shooting world with the term “tactical” a few years ago, and it hit our world just as hard. No matter—it’s a natural period of adjustment, and soon the word overlanding will seem no more odd than the word camping did 30 years ago.

Despite numerous attempts at narrowly defining the term, however, there remains a skeptical contingent who fail to see anything but marketing differentiating “overlanding” from “camping.” If you’re among those skeptics, we offer here, tongue firmly in cheek, this simple guide on the subject:

If you have a sleeping bag and tent in the back of a pickup, that’s camping.

If you have a sleeping bag and tent in the back of a Land Rover, that’s overlanding.

And, finally,

If you have a sleeping bag and tent in the back of a Land Rover with your name stenciled on the door, that’s an expedition.

Whatever your own definition, just make sure you get out there and participate!

Header collage credit: Roseann Hanson