Quick Take: Royal Enfield takes on all comers in the 450cc class with a new version of the Himalayan. With a new modern engine, Showa suspension, ABS, ride modes, a high-tech display and a price substantially lower than many competitors, the tough but attractive Himalayan 450 makes entry into the world of real-deal adventure motorcycling easier than ever. Start planning your big adventure.

– William Roberson

Renowned climber and adventure guy Owen Clarke dropped off the 2024 Royal Enfield Himalayan 450 for this review after blasting around Utah and then Central Oregon on the new adventure machine from India. When he pulled up, I had to laugh: It was Royal Enfield Press Bike Number 5, the exact same Hanle black and gold Himalayan 450 I had ridden – and crashed (below) – on a press launch in Utah some weeks prior.

The crash bent the rear brake lever up 90 degrees and tweaked the handlebars a bit, but I bent the mild steel brake lever back into service trailside and finished out the Utah ride without any additional miscues. Definitely a tough bike – and one that impressed me so much that after the Utah ride, it topped my list to replace my venerable 1995 Suzuki DR650SE, which will turn 30 this coming year.

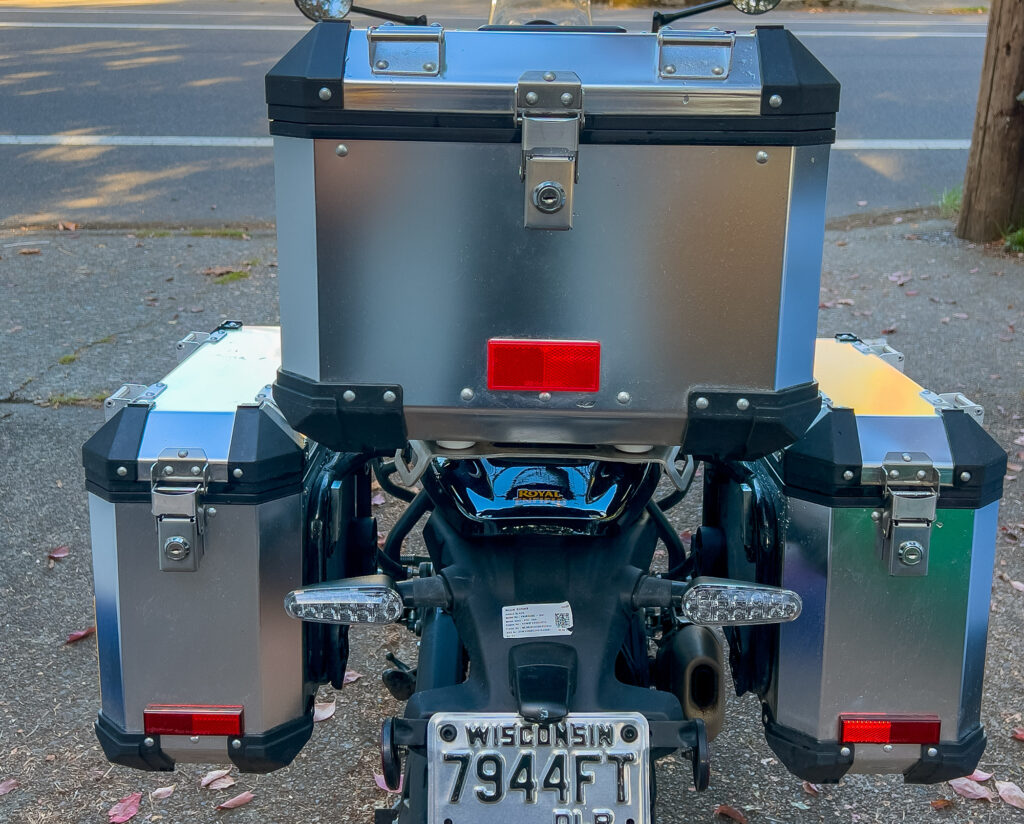

All patched up, the company added a triplet of OEM aluminum panniers as part of its “Adventure Package” option and sent Number 5 on its way to Clarke, who also downed it on his travels, but without any damage. The $2,400 Adventure Pack includes three aluminum panniers with mounting racks, lower crash bars, radiator shield, Hanle black and gold paint, upgraded seats, a larger windscreen, a pannier liner bag, and a bike cover. The lower crash bars were still nicked up from my crash, and Clarke delivered it covered with a coating of Oregon mud, so in repayment for the abuse it had received, I gave it a thorough scrub. Save for a few nicks and scratches, it cleaned up pretty well, and as adventure bikes go, it’s a good-looking rig. Would it still impress over a weekend ride-and-camp adventure on those stock tires?

Royal Enfield Powers Up

The new 40-horsepower liquid-cooled “Sherpa” motor – the most modern engine Royal Enfield has ever produced – also makes a solid 30 pound-feet of torque. Unlike its 411cc predecessor, the Himalayan 450 is right at home going 55, 65, or 85 miles an hour. It can touch triple digits in the flat, even with packed panniers and a full-size taco-addicted rider aboard. As such, legal highway speeds in the tall sixth gear are blissful. It’s a big step up from the comparatively wheezy air-cooled mill and five-speed transmission of the original Himalayan 411, which couldn’t reach 80 mph going downhill with a tailwind.

Mt. Adams looms in the distance on the rural plains of southern Washington. Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

For comparison, the Himalayan 450 makes a bit more power than Honda’s new CRF450L – which costs thousands more. Additionally, the new 450 sports a Harris Performance-designed steel tube frame and Showa suspension with a preload adjustable rear monoshock. Front suspension is not adjustable, but since it is Showa and the bike itself is rather inexpensive, riders can upgrade the front forks and still keep costs reasonable. However, I found the front forks to be pretty much spot-on for road riding and all but the most aggressive off-roading. Still, some fork preload ability would be nice when loading up the bike with a passenger and gear.

READ MORE: Review: Midland GXT67 Pro GMRS Radio

Gone, too, is the busy 1980s-style cockpit of the 411 Himi, replaced by a single round 4-inch “Tripper Dash” digital display that can show GPS maps when paired with the Royal Enfield smartphone app and a USB cable. However, I struggled to make it work consistently and eventually reverted to using OnX and Gaia on my iPhone to find a good campsite. In “regular” mode as seen below, the Tripper display features an analog tachometer, digital speedometer, gas gauge, clock, gear position, and an array of sub-display options, including range to empty, engine coolant temp, MPG data, and more.

A small joystick on the left bar toggles the display options, but changing to GPS view and some other options requires the bike to be stopped, which I understand from a safety perspective but still found a bit annoying.

Riding In Volcano Alley

I set out early on a Saturday morning with a plan to go on a quick overnight camping trip via some back roads that split through the Cascades volcanoes while the roads (and trails) were still dry. The cold morning air meant Oregon’s weather was quickly turning from late summer toward the damp fall, but dry conditions were expected to hang on for the next week.

All loaded up, I headed north on Interstate 205 out of Portland, then headed east through the Columbia River Gorge on Washington’s State Road 14, a twisting two-lane masterpiece that hugs canyon walls and traces along basalt massifs and redoubts along the Columbia River. Passing lanes are few on SR14, but at the early hour, traffic was light. I hooked left at Carson, Washington, to pick up the Wind River Highway, or as local riders call it: The Road to Randle.

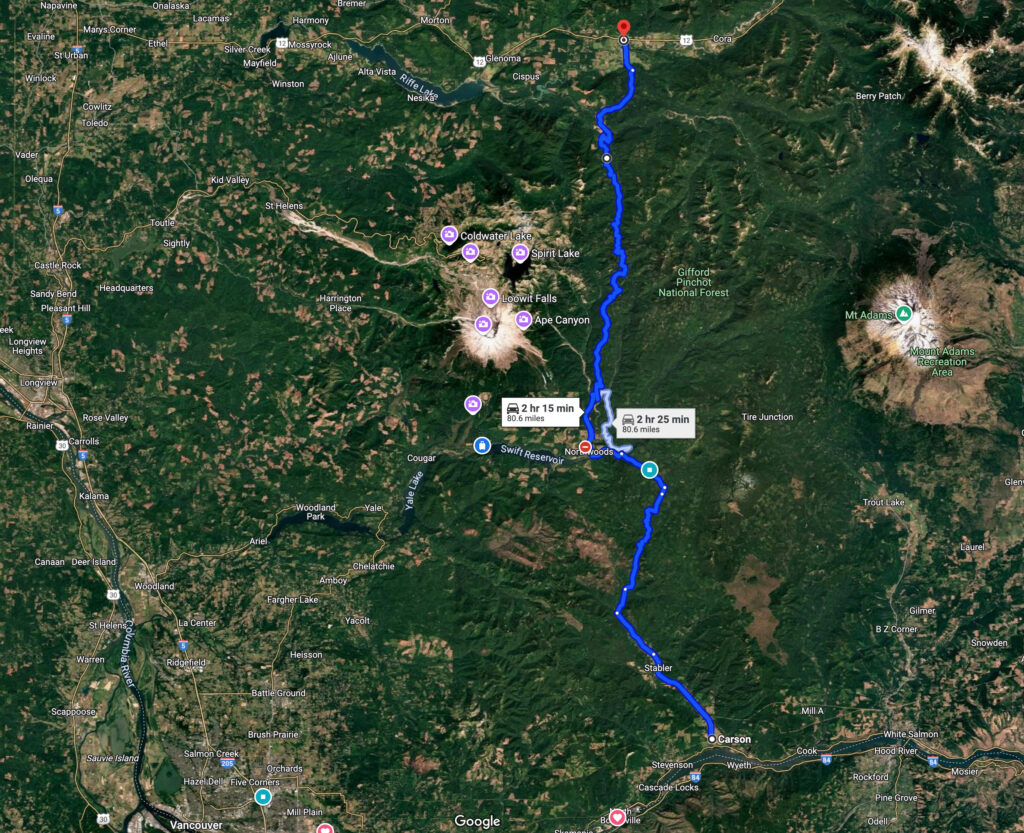

On a map (above), the roads that make up the stretch from Carson (bottom) to Randle, Washington (red pin, top of map) don’t look like they would take long to traverse, but ADV riders should set aside plenty of time for the trip. The (mostly) paved but curving network of tiny rural roads is highly technical and running off the pavement unintentionally will not end well. Riders will also want to make time for the many opportunities to make side journeys to lookout points and to explore forest service roads. It is perhaps one of the most amazing roads in the Pacific Northwest – when it’s open, which is only during the summer and early fall.

There are plenty of options to hop off the pavement and explore the huge network of forest service roads that lead to alpine lakes, secluded campgrounds, and scenic wonders, including the still awe-inspiring Mt. St. Helens volcano and her nearby dormant siblings: Mt. Adams to the east, Mt. Rainier to the north and Mt. Hood to the south just over the Columbia River in Oregon. However, I encountered an early setback. At Northwoods, near the Mt. St. Helens viewpoint, the road was closed due to a washout (not uncommon), but since I was on the 450, I thought just maybe if the washout was “minor,” I could go around the barricades and pick my way across if there was a passage. There wasn’t. The road was gone, with no safe alternative passage to cross the abyss, even if the Himmie 450 had been wearing knobbies. That’s the way it sometimes goes in volcano alley.

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Plan B was to take the light blue route on the map around the closure by way of a forest road, but a few nights before, the PNW Cascades had gotten a first blast of snow at upper elevations, which the forest road leads straight into. It was no blizzard, but the road was shadowed in most places and the few inches of snow remained, making it too slick to safely navigate on the pavement-suited CEAT skins while riding solo. I turned back and went with Plan C, a route I call the Two Mountain Loop, which traces past Mt. Adams and then crosses the Columbia River at the scenic town of Hood River, Oregon.

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Ticking along on (mostly) paved roads through tree tunnels colored by fall (above) and open tracts of farmland that dot the Cascades, the Himalayan 450 is in its element – especially since it is wearing those same OEM 80/20 (90/10?) CEAT tires that it had in Utah. When the off-road sections of the Utah ride were dry, they actually fared well.

Eventually, I pulled off the pavement and picked my way up to a distant campground in the Washington Cascades. The CEAT skins had a much better time of it on the much more grippy volcanic basalt gravel than the oil-slick wet clay of the Utah Rockies. I went around the few muddy sections and managed to keep the bike upright, eventually finding a cozy spot among the towering fir trees of the Great Northwest. Night fell, and I zipped up into my small tent. Frogs along a nearby creek lulled me to sleep. The campground was mostly empty since summer was over in the PNW, save for this one last weekend of clear weekend weather. Rain (and snow) was forecast to return in the next few days.

The morning arrived cold and clear, and in the past, a warm jacket and layers were enough to keep this camper cozy against the frost, but I’m getting older and seemingly less impervious to the cold. Lately, I’ve been trying out heated gear and on this trip I brought two key bits: heated pants and a heated vest by Kimimoto, who are perhaps better known for their saddlebags and such. But they have a new vest out that incorporates new materials that reflects body heat, and it runs for hours off an included battery pack via USB, so most portable powerbanks will work with it. The pants are worn as a liner/layer and use a proprietary powerbank and I was impressed with the quality and fit, and they will also plug into a 12-volt harness connected to your bike if you need long-term heating. Both included a clever D-pad that controls multiple heat settings in multiple areas of the pants and vest for customizing the heat output. Along with a pair of Tour Master Synergy heated gloves (also battery or 12-Volt) and a good neck warmer (which the Kimimoto vest can compliment), I was snug as a bug rolling out of the campsite in sub-40-degree temperatures.

READ MORE: The Best Gifts for Overlanders 2024

I followed my familiar but always beautiful (and still technical) route down through deep canyons and through small towns like Klickitat, named for the river that runs through it and the First American people that are still present in the area. Along the roadway, tribal members sell freshly caught salmon out of coolers from vans at a fraction of the price found in stores. I stopped and picked up some deep red salmon steaks that were carefully packed in ice and ziplock bags, and tucked them into a pannier. The cold temperatures would hopefully keep them fresh for the few hours I needed to get home, which included an expected cold passage to 4,000 feet as I circled Mt. Hood.

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

Photo by William Roberson

I reconnected with fabulous State Road 14 heading west, gliding along rock walls with the mighty Columbia River on my left. In this area, SR14 is a wide, sweeping two-lane passage that follows the shores of the Columbia. The speed limit is 55, but most drivers and riders go ten over (or more), and the 450 rolls along in comfort at 65 to 70mph. Eventually, I arrived in Stevenson, Washington, across the river from Hood River, one of the earliest settlements in Oregon. The towns are connected by the Hood River Bridge, which celebrates its 100th birthday this December. It is a product of its time: harrowingly narrow, with a transparent steel grate for a roadway that stretches over 4,400 feet, most of it just a few dozen feet above the waters of the Columbia, which are placid today thanks to multiple hydroelectric dams. Back when it was built, the Columbia River was still a wild and flood-prone waterway with rapids, waterfalls, and jumping salmon headed out to sea or back to the headwaters to spawn. Today, Hood River is a wind and kite-surfing mecca due to the dam-flattened water and the reliably gusting winds through the Gorge. Still, crossing the bridge is not for the faint of heart, especially when the wind is howling, but on this morning, it’s just breezy, and I thread the 450 past semis and SUVs struggling to stay in their too-small lanes across the span.

Once across and having paid the $3 toll, I gas up, get some breakfast at a food cart, and point the 450 up Oregon Highway 35. The city of Hood River sits at about 280 feet above sea level; in less than an hour, I’ll be crossing the pass at Government Camp, which is right at 4,000 feet. Skies are sunny, but nearby late summer wildfires have tinged the blue with smoke, and the usually majestic Mt. Hood appears like a towering specter in the haze, perhaps fitting for a dormant volcano just a few dozen miles from its explosive partner, Mt. St. Helens.

Traffic picks up a bit but the 450 has no trouble accelerating to well past 55 mph up the grade as it spins up in fourth or fifth gear. The Sherpa engine nears its 9,000 rpm redline as I slingshot past chugging RVs and trucks at well over the legal limit, and some vibration seeps through the footpegs and bars, but it’s only just noticeable and not intrusive, and certainly at a lower level than my DR650SE. Cresting the pass where skiers exit to climb another 2,000 feet to iconic Timberline Lodge and its many ski runs, I click to sixth gear and begin heading down the grade towards mountain towns like Zig Zag, Wemme, Welches, and Sandy that dot Highway 26 on the way back into Portland. Turn after turn presents a close-up view of the 11,250-foot Mount Hood, and some cars sway across lanes as drivers try to snap cell phone photos while navigating. Highway 26 can be a bit of a blood alley as it requires full concentration to navigate safely, and I give the many Subarus and Broncos a wide berth until blasting past on straight sections. I am thankful for the 450’s power and handling as I finally arrive in Sandy, which marks the entry and exit from the Mount Hood wilderness area. Highway 26 grows to four lanes and becomes busy with traffic as it leads into Portland, and soon enough, I’m back in my driveway, hosing the mud off the Himalayan 450 before another press member arrives to pick it up the next day.

One Size Fits All?

Despite my crashing this particular bike in Utah and Clarke’s similar hard riding during his review period, sturdy Number 5 ran flawlessly during my review. I bought a Royal Enfield INT650 in 2020 after reviewing it for another publication as I was impressed with the bike’s style, quality and easy rideability. As I learned more about Royal Enfield – and even got a chance to ride the Super Meteor 650 in India – I’ve come to appreciate the company’s philosophy around motorcycle design. In India, motorcycles are beasts of burden. They must be simple, reliable, affordable, tough, and affordably repairable to survive the brutal riding conditions in India. Huge power and high speed are very low on the priority list – in India. As Royal Enfield focuses more on markets outside of India, they recognize that in many places, some poke and power are higher on the “want” list. Thus the Himalayan 450.

With the 450, Royal Enfield has remixed the lovable – but too slow and basic – Himmie 411. The new, modern engine sports power output that equals, exceeds, or achieves parity with many of the other 450-class bikes now on the market or arriving soon. While bike makers already selling in the North American and EU markets often get caught up in competition over who can squeeze the most power from an engine, Royal Enfield’s approach still clearly errs on the side of usability and dependability. But the Sherpa motor, Harris-designed frame, Tripper tech and Showa suspension stir in both modern performance and surprising on and off-road capability that compliments the overall toughness and working-dog nature of the 450.

As a bonus, the Himalayan 450 is a stylish mount, and that’s saying something for an ADV bike. The Hanle black and gold color scheme adds $100 to the price and is well worth it. I said in my first ride review that I’d be buying one at some point, and the longer test ride through my home turf only reinforces that decision. The Himalayan 450 is a great combination of performance, comfort, capability, style, and affordability. Competitors should be on notice. Expect to see it in my motorcycle overlanding travel stories in the future – but likely with different tires.

What to Know:

2024 Royal Enfield Himalayan 450, base MSRP: $5,999 As tested with optional OEM Adventure Pack: $8,136

Adventure Pack includes three aluminum panniers with mounting racks, lower crash bars, radiator shield, Hanle black and gold paint, upgraded seats, larger windscreen, pannier liner bags, bike cover.

- New liquid-cooled, 4-valve 452cc ‘Sherpa’ engine is modern, powerful, and competitive

- ABS, slipper clutch, six-speed gearbox all come standard

- No more highway speed or passing anxiety as on the older Himalayan 411

- Very affordable, leaving room in the budget for needed ADV accessories like panniers, etc.

- Showa suspension covers most any situation but lacks front fork adjustability

- Clever ‘Tripper Dash’ instrument is useful and multi-functional, but GPS/smartphone setup can be finicky

- Lower-mount exhaust means panniers are full-size on each side

- Roomy and comfortable with adjustable seat height and several OEM seat options

- Wire wheels that take tubeless tires are on the way as an option

- Stock CEAT 80/20 tires are not ready for challenging off-road passages but are good on pavement and dry dirt/gravel

- Stock 4.5-gallon tank can just clear 200 miles of real-world mixed riding range

- Stock bash plate is plastic and should be upgraded to metal

- Pretty good looking as ADV bikes go, especially in black and gold (+$100) Hanle color scheme

- Cruise control and a bit less weight would be nice

SPECIFICATIONS:

Engine: Single Cylinder, DOHC with four valves, liquid-cooled, fuel injected

Displacement: 452cc

Compression ratio: 11.5:1

Max power: 40hp @ 8,000 rpm

Max torque: 30lb-ft @ 5,500 rpm

Clutch: Wet multiplate with Slip and Assist

Gearbox: 6-speed, chain drive

Fuel system: EFI ride by wire throttle

Frame: Twin-spar tubular steel

Front suspension: Showa USD 43mm forks with 7.9 inches of travel, not adjustable

Rear suspension: Showa Monoshock with 7.9 inches of travel, preload adjustable via stepped collar

Wheelbase: 59.44 inches

Ground clearance: 9.1 inches

Stock seat height: 32.5-33.3 inches (two positions offered)

Curb weight (fueled): 432 lbs / 196 kg

Fuel capacity: 4.5 gallons / 17 Liters

Front tire: 90/90-21-inch CEAT

Rear tire: 140/80-17-inch CEAT

Front brakes: ByBre (Brembo) 320 mm disc, two-piston caliper

Rear brakes: ByBre (Brembo) 270 mm disc, single-piston caliper, dual-channel ABS, rear-wheel deactivation option

Electrical system: 12V Volt DC with USB-C powerlet on handlebars

Head lamp: LED

Tail lamp: Integrated LED turn signals and tail light