KICKSTANDS & KEVLAR

Kickstands & Kevlar is a blog hosted by Overland Expo’s own Motorcycle Community Ambassador, Eva Rupert.

Follow Eva @augusteva.

For years my daily driver was a well worn 2009 BMW F800GS. And it is clearly an adventure bike. It was obvious in every category: knobby tires, long-travel suspension, durable luggage, and all the nicks, scratches and gnar to prove that it occasionally hits the ground in rugged terrain.

That said, I guarantee that if you ride a motorcycle, you ride an adventure motorcycle.

I’m not saying that you must ride a GS or a KLR650 or a street-legal Frankensteined enduro. But, in my humble and wanderlusting opinion, every motorcycle is — on a fundamental level — an adventure bike.

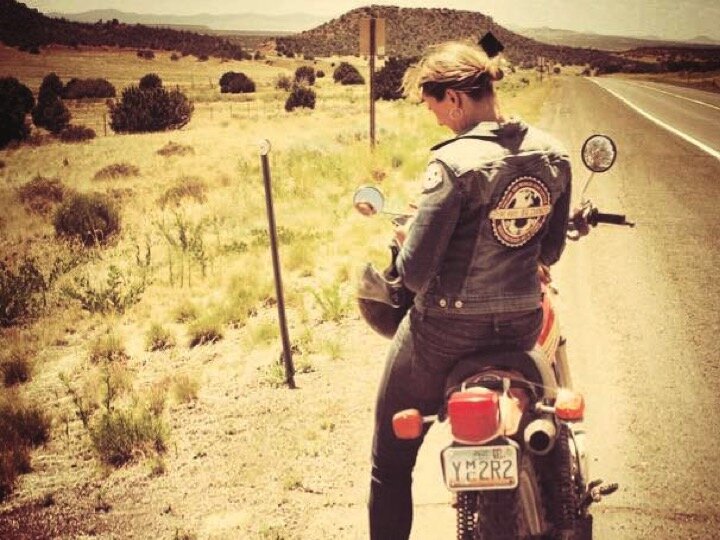

The first time I went to Overland Expo, I strapped my duffel bag to the back seat of my 1979 Honda CX500 and rode out to Mormon Lake. I had just moved to Flagstaff from Estes Park, Colorado and the thought that my trusty CX wasn’t an adventure motorcycle had never dawned on me.

Navigating my beloved vintage machine along the lumpy lakebed road into Moto Village at the far end of the exhibitor area, I found myself surrounded by real adventure motorcycles. The field was full of giant, farkled-out machines wielded by spacemen standing on their pegs. They had luggage that didn’t require an intricate system of bungee cords to keep things in place. Their motorcycles were probably even built during this century, a far cry from any bike I’d ever owned at that point.

As if I wasn’t out of place enough already by riding my old cruiser to Overland Expo, I was at the event to meet my buddy, Josh. We were going to spend the weekend promoting the crazy charity idea we had schemed up over cajun tater tots and beers at Satchmo’s BBQ a couple of months prior.

Josh and I were both recent transplants to Flagstaff and had become fast friends over a shared love of vintage bikes and snarky humor. Josh had a 1972 Honda CB100 that was collecting dust in his storage unit and I was eyeing a Trail 90 as companion to my CX. We were both up to our chinstraps in work and craving an adventure. As we doused our tots in remoulade, we decided that we would take those little bikes on an inappropriately long ride and use our foolishness to raise some money for a good cause.

We pitched our popup tent for the weekend alongside the other moto exhibitors, strung up our Tiny Bikes: Big Change banner, and spent the weekend explaining why we would be riding from California to New Mexico on our ridiculously small, and obviously unfit for adventure, motorcycles.

We just want to see if we can.

And that, my friends, is what adventure motorcycling is all about. Riding is simply steeped in adventure and we should dispel all myths that you have to have the latest KTM 790 to go on an adventure ride (although, if anyone at KTM is reading this, I’d be happy to take one of those 790s off your hands).

The need for adventure is a basic human instinct. At some point in humanity’s history we no longer had to worry about keeping the cave fire stoked and fighting off saber tooth tigers, as we migrated on foot across the savanna. But we were still wired for exploration. After millena of traveling by horse, yak, and camel, we were bound to come up with something that was as fun as it was practical for transportation. Enter the motorcycle — that brilliant feat of human innovation.

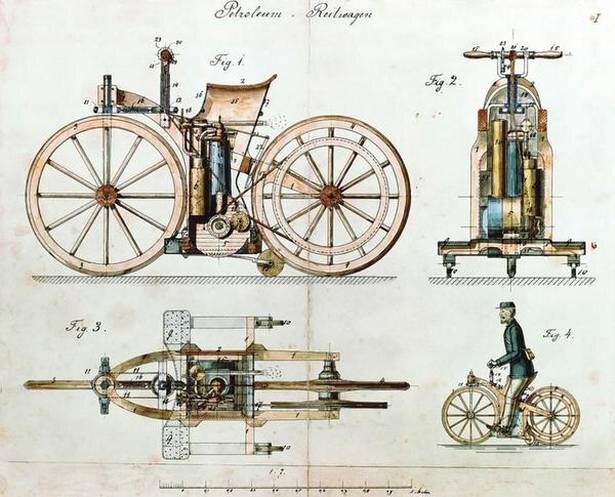

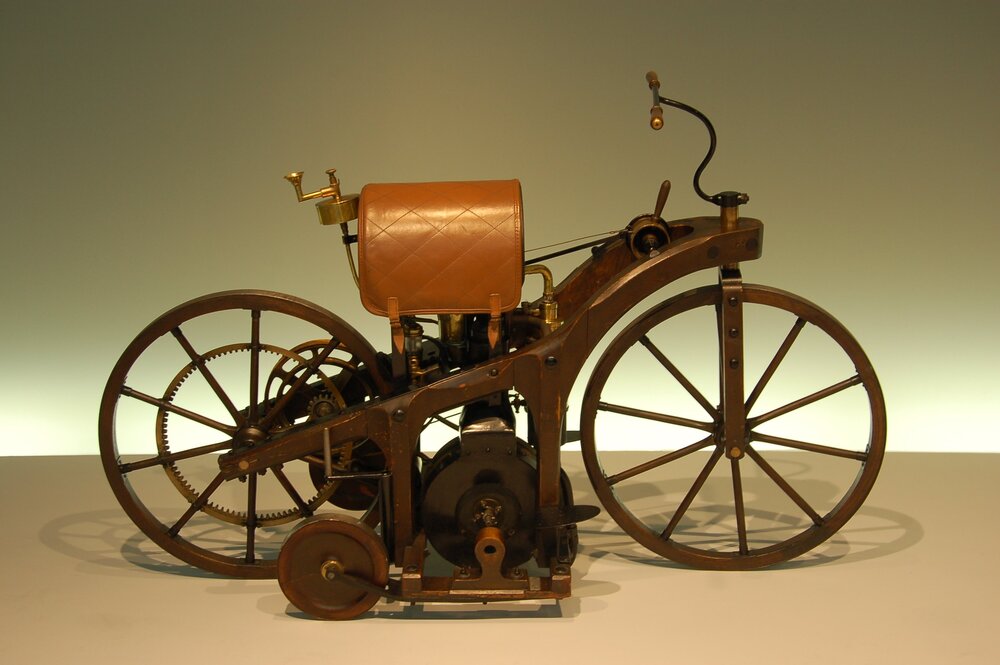

Let’s take a moment to consider the origins of two-wheeled motorized travel. Though the internet can’t seem to agree on which of the early bastardized bicycles is actually the first motorcycle, what’s clear is that all of the early motorbikes are a pure exercise in adventure. These early inventors were treading in uncharted waters and pioneering in ways we can hardly imagine today.

The origin of motorcycling is often attributed to Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach, but prior to the invention of their “Reitwagen,” Sylvestor Howard Roper created his coal-fired, steam-powered “velocipede.” Built on what was essentially a bicycle frame with a steam boiler under the seat and twist-grip throttle, the machine put Roper in an early grave at the age of 73 whilst proving that he could hit 40 miles per hour on the track. Although historians (those with far more credibility than myself) often exclude his steam engine from motorcycle history, I have to give this guy credit for motoring around on two wheels long before the big names stole the spotlight.

By 1885, coal engines were getting to be so 1860s, so Daimler and Maybach, a pair of German inventors, created the Reitwagen with outrigger wheels (training wheels for your GS, anyone?). The Reitwagen featured hot tube ignition: a platinum tube running into a combustion chamber, heated by an external open flame (that sure seems safe). Thus the internal combustion engine was born. From what I can tell, no journeys of great length were ever taken on the Reitwagen. Although the inventor’s son did ride it almost five miles one time and achieved the impressive speed of seven miles per hour.

With the Industrial Revolution in full swing, around the start of the 20th century, fuel-injected motorcycles began pouring off the assembly line by the dozen. World War One brought a massive boost to motorcycle manufacturing and drove the fledgling industry worldwide. During WWI, motorbikes were used for everything from moving ammunition to evacuating the wounded to couriering messages between units. If you think riding a BDR is adventurous, try riding on the front lines during trench warfare.

When Josh and I took off for our ‘Tiny Bikes’ ride, it was hardly trench warfare. But it was a blazing 108 degrees in the lowlands of the Sonoran Desert. We had collected a group of friends who also had bikes that fell into our definition of tiny: sub-200 cubic-centimeters. Our ragtag posse of four old Hondas were accompanied by Josh’s mom; Joy was driving the motorhome and pulling a flatbed trailer — just in case. We donned our gear and headed east over sweltering pavement across Arizona and began the process of rattling loose every bolt on our little bikes. Our top speed of 40 mph hardly cooled us off as we made our way no faster than Roper’s velocipede.

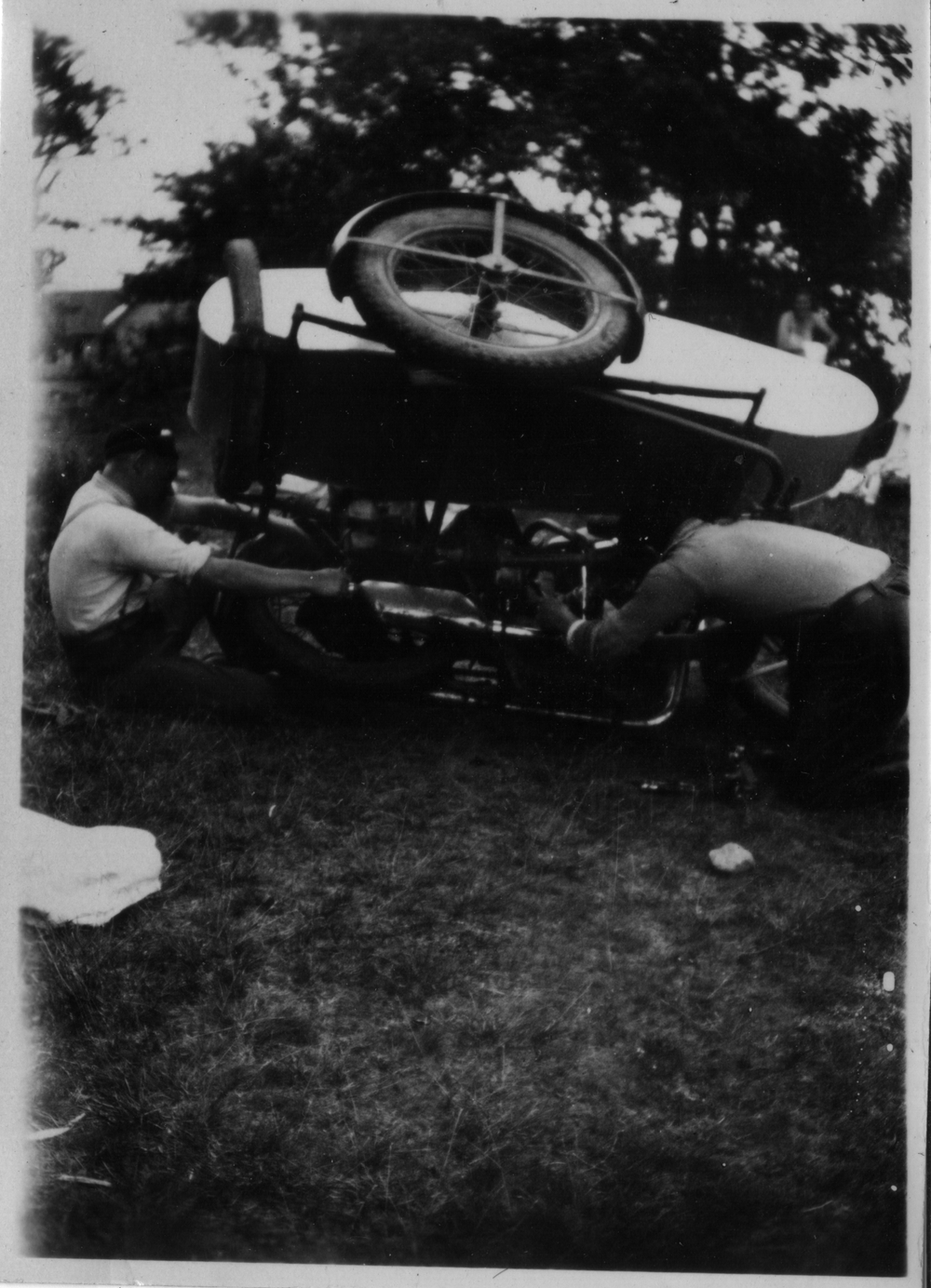

Our journey, like all great adventures, was fraught with mechanical trouble. Fortunately, Josh’s favorite pastime is restoring old things: mostly motorcycles and the occasional vintage lawnmower. His roadside mechanical prowess proved invaluable throughout the trip and he spent almost as many hours swapping spark plugs, changing out carburetors, and replacing the starter in the rescue motorhome as he did riding.

Despite Josh’s wrenching skills, my shiny new 1976 CT90 ended up with an unrepairable rectifier issue and spent the rest of the trip on the trailer. I swapped bikes with Nadji, who prefers her moto miles on dirt anyhow and certainly didn’t balk at the air conditioned comfort of the motorhome. I ended up continuing the journey on her ‘79 Honda XL200.

I almost hate to admit in public that we had a support vehicle along on our ride (can I save face by assuring you that I haven’t had one since?). Especially considering that 111 years prior, George Wyman took his leather belt drive, wooden wheel, 1.5-horsepower motorized bicycle across the entire country. He covered 3,800 miles over the course of two months, completely unsupported. His account of the journey is a fun read. It is the kind of story that makes you want to pack your panniers and hit the road — on the comfort of your fuel-injected GS with cross-spoked wheels and heated grips, that is.

The list of adventure riding throughout the 20th century is impressive, to say the least. Carl Stearns Clancy circumnavigated the globe in 1912. Hungarians Zoltán Sulkowsky and Gyula Bartha traveled through six out of seven continents and put over 100,000 miles on a Harley Davidson sidecar between 1928 and 1936. Max Reisch outfitted his 250-cc Puch in 1933 with a large format camera, typewriter, and pillion friend. He set out from Vienna to Mumbai, completing the first overland journey from Europe to India. Notably, Reisch can also be credited for beginning the historic overland tradition of packing everything but the kitchen sink. Meanwhile, the BMW R80 G/S, the first ‘real’ adventure motorcycle, was still a half century away from being invented.

The thing that fascinates me the most about these early moto-travelers is how raw their adventures were. They had no proverbial safety nets to speak of. In the first quarter of the century, outside of the cities, roads were rudimentary at best and often nonexistent. You purchased your gas from the chemist’s workshop. There was no Garmin or Butler Maps to plot your course. There were no online forums to consult or Overland Expos to attend to get the inside scoop on what might be in store for you. You just packed a simple kit and hit the road with your wool jacket, handgun, tools, and the occasional 50-pound typewriter. There were no knobby tires, overnight parts delivery from Revzilla, or waterproof Klim suits. Josh’s mom was definitely not driving the motorhome to pick up the pieces.

There is nothing contrived about these early journeys; you simply pull out of the driveway, pick a direction, and let the adventure unfold. Nowadays our world is so developed, regulated, and safe. We have handrails around everything and safety precautions ad nauseum. How then are we to have a proper adventure, an unusual and exciting, typically hazardous, experience or activity? Unlike the early moto-explorers we have to put in a different sort of effort to create our adventures.

Now we have to push our creativity in order to push our comfort zones. Our world is so different compared to when Florence Blenkiron and Theresa Wallach set off from London to Cape Town in 1935 on their Redwing Panther with a sidecar and trailer. We have such a secure infrastructure, even in the wildest places, compared to what they encountered.

“Motorcycling is a tool with which you can accomplish something meaningful in your life,” Wallach said. “It is an art.”

The spirit of our adventures are the same now as they ever were. It starts with a question, a curiosity, an inquiry into the boundaries of our limits.

We just want to see if we can.

I believe that it is our responsibility to live fully and, with that, comes the need for adventure. To be clear, high-speed lane splitting during rush hour in Los Angeles can certainly feel like an adventure. But that is pure adrenaline. The sort of adventure I’m referring to is adrenaline-producing, but in a way that also involves curiosity, ambition, and stretching yourself culturally, physically, and emotionally.

Adventures do not require one-way plane tickets to the other side of the globe, they do not require weeks or years, gobs of money, or high-tech adventure bikes. Adventure is a state of mind and your motorcycle, whatever make and model it may be, is the vehicle. You already have everything you need. Whether on your GS or your Trail 90, you simply need to set your sights on something that captures your imagination, pull out of the driveway, and let the adventure unfold.

We have people to follow in the footsteps of like Ted Simon circumnavigating the globe on his Triumph Tiger and Helge Pederson logging a quarter million miles on the R80GS during his 10 Years on 2 Wheels. But even if we’re not pioneers in long-distance travel, our adventures can still be authentic if we keep the spirit of inquiry at the forefront of our minds.

Are you doing something unfamiliar that will push your mental, physical, and cultural comfort zones? Do you have an open mind? Are you riding a motorcycle? If you answer ‘yes’ to these questions, you are most certainly riding an adventure motorcycle.

After shaking off the uneasiness of our mechanical troubles, Josh, Wade (on his 1969 Honda CT90 that somehow ran flawlessly the entire trip) and I carried on towards New Mexico. Our struggles were rewarded with that sort of delicious riding we all live for: perfectly cool temperatures in the high country, pristine dirt heading east out of Prescott, the freshness of ponderosa pine wafting through our visors along the Mogollon Rim.

We spent our evenings laughing around the campfire about how to achieve the perfect racing tuck position on a CT90 and about the look on the faces of the bewildered Germans on shiny rental Harleys as our motley crew pulled away from the gas station.

When Josh and I left for our Tiny Bikes ride, we just wanted to see what we could do with a handful of days and our most improbable motorcycles. There was never a doubt in our minds that what we were doing was an adventure. It certainly didn’t land us on the grand list of motorcycle history or pave our future as Marxist revolutionaries (that’s a Che Guevara reference, of course), but our Tiny Bikes ride is one for our own personal history books.

Shortly after that first Overland Expo, I did end up getting a couple ‘real’ adventure bikes, a KLR650, followed by a couple of GSs. Of course, I still have my vintage Hondas. But they spend more time in the garage than they do out on the road, overshadowed by my fancy BMW.

Writing this makes me feel a little nostalgic for the days when it was just me and the old Honda meandering around in a big unexplored world, rearranging the bungee cords on my duffel bag, without a doubt in my mind that I was riding an adventure motorcycle.