This story originally appeared in the Overland Expo Sourcebook 2022.

By: Bill Dragoo

“Here, try this.”

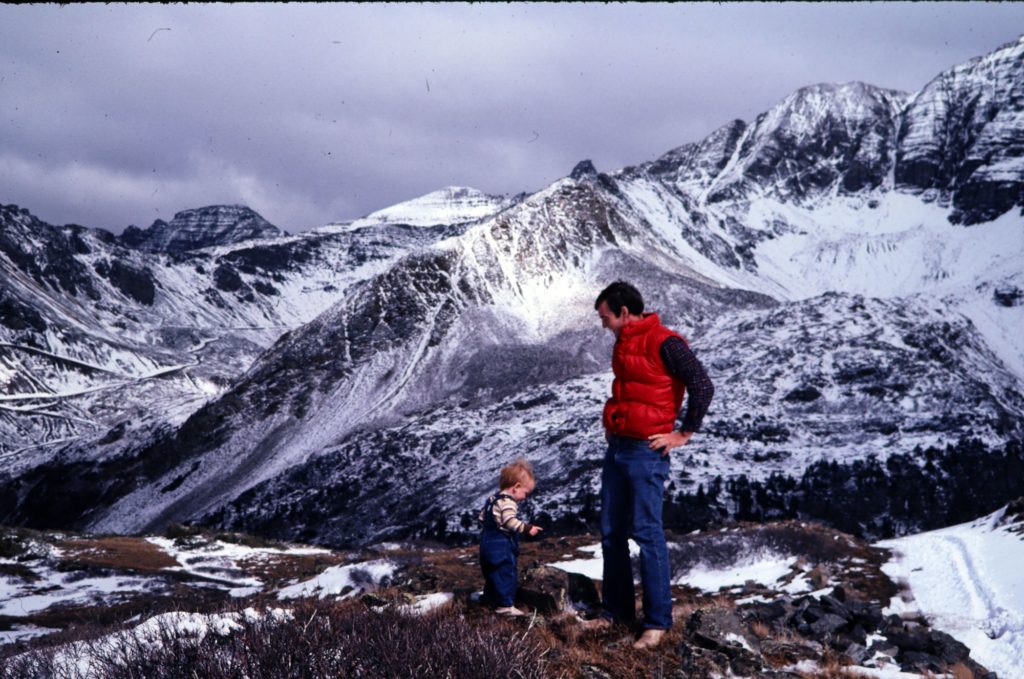

With one hand, my pregnant wife Skye leaned over and handed me the plastic top to our son’s car seat. Her other hand held our 14-month-old son, Jake, where he sat perched on her hip. His little brother, Ben, was just a bump in her belly, four months yet from emerging into a world of adventure. We were stuck in a snowdrift on the side of a switchback on Colorado’s Pearl Pass between the road to Independence Pass and Aspen. The sun had long since gone behind the mountain.

It wasn’t Jake’s first kerfuffle. Twelve months earlier, we had camped on Black Bear Pass in a blizzard at Ingram Lake above Telluride, just up from the dreaded switchbacks. We had climbed them backwards, against the flow of traffic and the law, following uncertain directions from a friend who had explained that the pass was one-way but couldn’t recall with any certainty which way that was.

Mercifully, that evening in October of 1980, there wasn’t any traffic. Apparently most would-be Jeepers had better sense than to tackle the perilous pass that time of year at that time of the evening.

The night before, we had slept in a ravine within view of the eternal torch at the refinery west of Borger, Texas, his very first camp-out at two months of age. I learned then that sleeping in a pup tent with a mom who is learning to nurse her first child can disrupt one’s rest unmercifully. The lesson was reinforced with vigor that night above Telluride as his mother tried to feed him in the cramped quarters of our little tent at sub-freezing temperatures. No wonder some animals squash their offspring in the den; it’s not an accident.

A year later, snowflakes fell in bulk as we left timberline and engaged the talus slopes of Pearl Pass. In our twenties and being from Oklahoma, driving in these rugged mountains was as fresh to us as the 11,000-foot air we breathed.

Our year-old, 1980 model Jeep CJ-7 seemed formidable, at least to our fledgling minds. It had a limited slip rear differential, 31×10.5×15 Goodyear Wrangler Radials and the secret weapon, a WARN 8274, 8000-pound winch bolted to the front bumper. This was our overlanding rig … although we had never heard the term, and we thought we were invincible.

READ MORE: First Overland Adventure: Bighorns, Bears, Truck Beds & Blue Highways

That was until the blizzard hit.

We extracted ourselves from the snowdrift using our baby-seat shovel and dodged the next one by attaching our winch cable to a Jeep-sized boulder on the road above and winching between switchbacks.

Junior-high science class and 20 years of playing with rocks had left me with the impression that the density of a medium sized boulder was greater than the density of a CJ-7.

“That oughta hold,” I announced to a trusting wife and a kid who was fascinated at the amusement-park feeling of lying back against the seat while being suspended almost in mid-air — like the WARN ad that now hangs in my garage. Skye stared at the sky, silent as though speaking would make us and our situation heavier.

We staked our lives on my assessment, ignoring the laws of physics that, had we paid attention, would have said it didn’t take all that much to dislodge a rock from a slope with a winch/Jeep pendulum. We were headed for Aspen by way of this trail and, by golly, we had every intention of making it come hell or high water.

We got lucky and the rock held its ground. Our dreams were soon dashed, however, when ever-deepening banks of snow, old and new, and slippery side slopes finally soaked into my testosterone-addled brain like the saucer-sized snowflakes melting on my neck.

We made one more rockslide crossing by digging a narrow trench for our downhill wheels to ride in so we wouldn’t go off the side of the road. It worked, but even my cat would have been running the numbers on remaining lives by the time we decided to turn around. I made the executive decision that we had risked enough that night.

Winching down backwards wasn’t as hairy. Why worry about what you can’t see, right? We unhooked once we felt certain the Jeep wouldn’t drop beyond the narrow roadbed, squirmed the rig around to align with the road, and started back downhill.

Darkness closed in completely as we crept along, dim, yellow headlights struggling to punch a hole in the hypnotizing shower of whiteness. It was like sticking your head inside one of those snow globes with mountains and a little gingerbread house and someone shaking it.

I was spent. We were all hungry and climbing in and out of the Jeep so many times rendered the marginal heater even more marginal, plus the windshield was icing up around the edges, making vision a guess at best. We were cold and needed sleep.

Sliding off the road meant not getting to choose where we slept and the Jeep was cramped enough, sitting on its wheels. Nothing about trying to make a bivouac on top of a roll bar was of the least interest to me or my trusting spouse and child, all of whose trust was waning. I picked what looked like a flat spot as soon, as we dropped back below timberline and set out to set up camp.

READ MORE: First Overland Adventure: Fences Through the Kalahari

We had borrowed a North Face tent from the same friend who had been unsure of which direction Black Bear Pass should be driven the year before. It was back during the experimental age of mountaineering tent-making and this particular geodesic dome-shaped tent had at least a dozen metal loops randomly sewn to various points on its surface. Several poles of different lengths were ostensibly designed to slip through the metal loops in a not-to-be-done-wrong order.

I stuffed a double-D cell flashlight in my mouth, so I could see to sort out the order of assembly while the wind tugged and yanked at the fabric like a poodle with a pillowcase. It’s hard to look cool when doing that. Finally, Skye plopped Jake back in his car seat, still wet from its parts being used as a shovel, and offered to hold the flashlight … in her hand.

My fingers lost all feeling and my bare head was soaked and my jaws ached from holding the light. At least my hair was still warm enough to melt the snow but I was certain the ice threshold was near. It was like getting an ice cream headache without the fun of eating ice cream.

I jammed a stake in the ground to keep the tent-from-hell from blowing away. The poles were pretty much wedged in places where they most certainly didn’t belong. I prayed they weren’t kinked because I did not wish to pay for a tent I never wanted to see again.

Jake started crying, and so did Skye. I joined in, sitting in the Jeep, trying to warm my hands enough to work the steering wheel. This was before I’d heard of Raynaud’s Syndrome. I just thought I was a wuss and aching white fingers were normal under these circumstances.

I considered leaving the tent there by the trail, but decided it would be best not to. I climbed out of the Jeep and tried to withdraw the poles. They came apart before I had withdrawn them from the loops. The bungee cords prevented further retrieval so I wadded up the whole mess and crammed it in back on top of Jake who was already wet and cold. He cried louder.

Skye defied decorum, unbuckled him from the security of his car seat and held him in her lap on top of Ben, who was still in her belly and, miraculously, was not born there on the spot. We eased our way onward with visions of warmth and safety floating dreamlike through our minds.

We had no idea where we would spend the night but as we emerged back onto State Highway 82, the dim glow of a vacancy sign pierced the blizzard. We pulled in and purchased the remainder of the night in a cabin from the kind woman who owned the place.

Years later, I was crossing Independence Pass with my third and youngest son, Tucker, on a pair of Harley Davidson Sportsters. Sleet fell as we made our way down towards Buena Vista and our hands were wet and cold. We found a cabin for the night near the entrance to Pearl Pass.

When we checked in, something felt familiar about the room. The woman seemed familiar, too. It hit me. She was the one … this was the place that had saved us from ourselves a quarter-century before when his two older brothers were almost rendered extinct by a dad hell bent on bouncing his babies through the snow, the hard way, to Aspen.

Bill Dragoo is founder of D.A.R.T. (Dragoo Adventure Rider Training), an internationally certified BMW Motorrad off-road motorcycle instructor, certified flight instructor, commercial seaplane and sailplane pilot, skydiver, scuba diver, overlander and adventure journalist. Always game for a challenge, Bill has won numerous competitions in motocross, cross-country mountain biking and sailboat racing. In 2010 he represented Team USA in BMW’s GS Trophy competition in South Africa, Swaziland, and Mozambique. Bill and his wife Susan love to explore the American West and beyond by motorcycle and in their purpose-built Gen 5 Toyota 4Runner as they research historic trails and traditions. He is quick to tell anyone that the synergy between overlanding, riding and writing has opened doors he would never have imagined as a younger man.