Quick Take: Canadian conglomerate BRP is introducing two new motorcycles under the iconic Can-Am brand, and has decided they will be all-electric, street legal machines, including an adventure bike model called Origin. Both models are based on a common architecture, and are competent, stylish, fun-to-ride machines, but come with the current limitations of an all-electric powertrain.

by William Roberson

Talk to any long-time motorcycle rider with a bit of grey in their hair (if they still have hair) about the motorcycles of their youth, and many will recall the race-winning dirt bikes and agile 250cc street bikes (below) from Can-Am, a popular Canadian motorcycle maker that was a subsidiary of snowmobile maker Bombardier in the 1970s. The Can-Am brand was shuttered in 1987.

Canadian powersports maker Bombardier Recreational Products – better known as snowmobile and off-road vehicle maker BRP – was spun off from Bombardier in 2003 and resurrected the Can-Am brand in 2006 with a line of four-wheel ATV/UTVs and then added the new Can-Am Spyder street-legal three-wheelers in 2007. BRP also produces Ski-Doo snowmobiles, Sea-Doo personal watercraft, Alumacraft boats, and other power sports brands, but until now, it has not produced any motorcycles.

Both new Can-Am motorcycle models, called Origin and Pulse, are fully electric and based on a common platform. BRP executives I contacted hinted strongly that more models are in the works, but the Origin and Pulse are now in production.

While I recently rode both bikes, I spent most of my time riding the Origin adventure bike, including some dedicated time on a technical dirt track. I also got a tour of the facility where Can-Am developed and designed the production motorcycles.

Can-Am Electric Motorcycle Tech

As noted, the Origin and Pulse share the same basic architecture, and some of it is unusual and has not been seen on motorcycles before. Can-Am, with help and oversight from BRP, certainly wanted to use innovation to differentiate themselves from the competition, and a lot of the tech and design of the bikes was influenced by BRP’s extensive experience in building Ski-Doo snowmobiles, including electric snowmobiles, which they have been producing for several years now.

READ MORE: You Can Win Awesome Prizes at Overland Expo Mountain West

Like those electric snow machines, motive power for the Can-Am motos comes from a Rotax-built liquid-cooled electric motor. Engine and motor builder Rotax is a subsidiary of Bombardier, Inc., which maintains a close relationship with BRP. Tweaked for motorcycle duties, the compact Rotax motor in the Can-Am bikes makes 47 horsepower and 72Nm/53 lb-ft of torque at 12,000 rpm, which may seem high for a gas engine but is a fairly average rpm level for an electric motor since it has no reciprocating parts.

Can-Am Origin, left, and the street-focused Pulse. Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

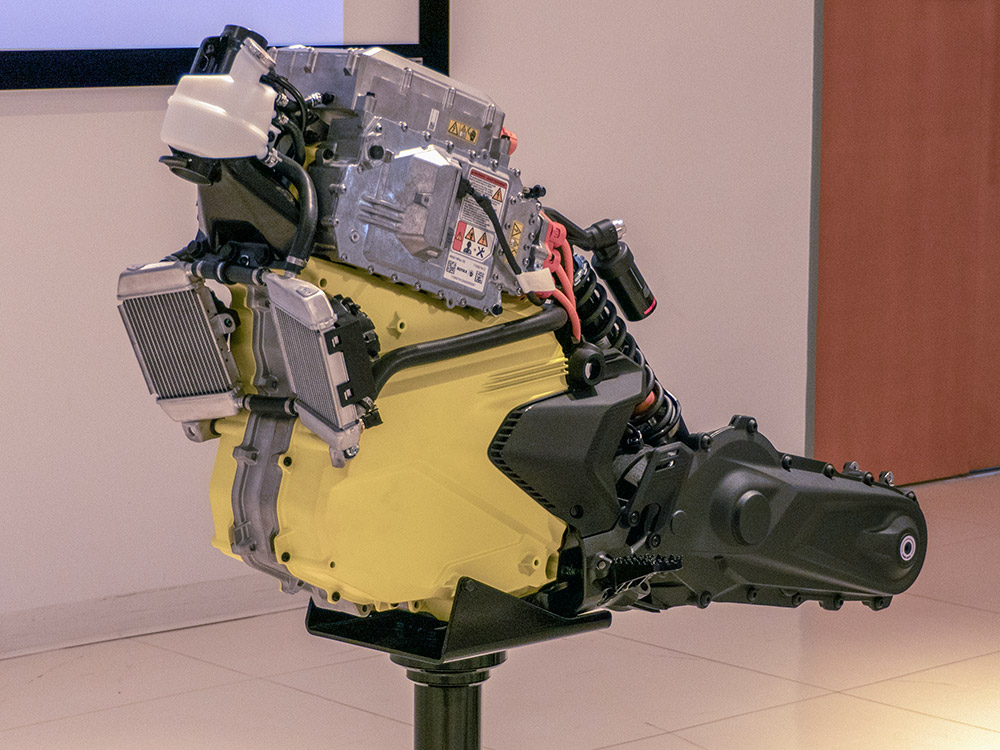

Electricity comes from a 8.9 kWh battery pack that forms the backbone of the bikes. Can-Am has neatly packaged the modern tech needed for battery vehicles onto the battery casing, including the DC to AC voltage converter, power regulator, and 6.6 kW charging module. Together, they form what Can-Am calls the PowerUnit Core (below). It’s painted bright yellow in a nod to Can-Am’s color scheme in the 1970s.

Photo by William Roberson

The electric motor itself, about the size of a large cantaloupe, is positioned at the swingarm pivot and partially resides within the swingarm, and spins one reduction gear to multiply torque output. This helps keep the motor small and efficient. The reduction gear connects to the rear wheel with a chain. There’s only the “one” gear and no clutch or gearshift, as is normal for electric motorcycles. Can-Am says the Origin can hit 60 mph in 4.3 seconds, with the Pulse a tick faster at 3.8 seconds due to different wheel sizes, tire types, shorter suspension, and slightly less weight. During my ride test, both bikes could comfortably achieve 90 mph.

Like many electric vehicles, the Can-Am bikes feature “regenerative braking,” better known just as “regen,” which briefly flips the motor from producing forward motion to energy producer for charging the battery. Can-Am has tweaked this feature to include multiple settings that imitate levels of engine braking, but they have also built the throttle to work in reverse as it were, by increasing regen when the throttle is rolled forward while “braking.” As such, while the bikes have capable J. Juan disc brakes with ABS, riders can extend riding range (and reduce brake wear) by using the variable regen feature as the brakes, as is common in electric cars with a “one pedal driving” feature. When slowing to a stop or going downhill, the bike’s speed can be precisely controlled without using the brakes while energy is harvested. To my knowledge, no other electric motorcycle has this type of variable regen feature. Of note, reverse mode at walking speed is a standard feature.

In another unusual move, Can-Am has enclosed the motor, reduction gear, chain and final drive in a single casing that also forms a single-sided rear swingarm for the rear wheel (below). This design decision allows Can-Am to have a bit more latitude with battery pack size and placement and simplifies the rear suspension and drivetrain to some degree. With the PowerUnit Core working as a stressed member, the rear swingarm and steering head connect directly to the pack’s casing.

While other motorcycle makers (Ducati, BMW, and Honda, for the most part) have models with single-sided swingarms, none of them also enclose the drive chain (or belt) within the arm itself, as Can-Am has with these new bikes. BMW typically uses an enclosed shaft drive system on most of its adventure bikes. A single-sided swingarm also makes rear wheel removal very simple, which is certainly a huge benefit for off-road riders who typically have to repair a puncture in locations far from any service.

The battery pack is cooled internally, and two small radiators located up high near the steering head shed heat instead of being placed directly in front of the engine as on a gas-powered moto. It’s a smart choice: Placing the small radiators up high also helps protect them from damage caused by debris coming off the front wheel, and in most impact/tip-over scenarios. It also eases filling the coolant.

READ MORE: Review: Ultimate9 evcX Throttle Controller

I asked Cam-Am’s team why they didn’t opt for a belt drive (as found on Zero’s electric DSRX ADV bike – and Harley-Davidson’s Pan America ADV model, among others), and they explained that they felt an external belt on an off-road capable bike was more vulnerable to failure if debris became stuck in the belt pulleys, which does make sense. Because of the large sprocket sizes needed with a belt drive system, it would not fit within a reasonably small enclosed driveline as the chain does now. The chain is kept taut (and quiet) with an idler wheel inside the swingarm, and an oil bath provides constant lubrication. Can-Am says maintenance of the sealed chain system, compared to the typical needs of an exposed chain, is very minimal.

The Origin rolls on an ADV-friendly 21/18-inch spoked wheelset that uses tubeless tires, with a KYB adjustable rear monoshock and KYB “USD” type forks with no adjustability up front. Both ends feature 10 inches of travel. Dunlop D605 tires come standard on the Origin. ABS and traction control also come standard, and the traction control can be turned off while only rear wheel ABS can be terminated. Front-wheel ABS can be minimized but not turned off completely in the off-road riding modes. This is typical and keeps the bikes in compliance with various worldwide safety regulations around ABS.

Both bikes include a cinematically wide 10.25-inch touchscreen (above) with multiple viewing modes, including Apple CarPlay. Connected to an iPhone, the display can show the usual CarPlay display modes, including GPS routing on the wide screen while retaining the speed and other vitals. Like many motorcycle touchscreens, most of the “touch” functionality is suspended while the motorcycle is in motion, so riders keep their eyes on the road ahead instead of poking at things on the screen while underway. To that end, a pod busy with buttons on the left handlebar allows riders to control the screen, music and voice controls without taking their hands off the bar. Can-Am is also offering a helmet with connected comms called “Vibe,” but we were not shown specific examples of the helmet. All lights on the bike are LEDs, including a twin-lens stacked front headlight array.

The styling of the bikes is clearly future-forward (and inspired by the snow owl, we were told), with angular bodywork available in three color combinations including Bright White, Carbon Black (+$500) and Sterling Silver in “73” trim (the best combo, in my opinion). Prices range from $14,499 for the basic models trim to $16,499 for the “73” luxe variant, which adds a short rally-type bug screen, striped wheels, badging, a cover and other bits.

Can-Am has published a series of four videos on the historical influence, development and tech for the new bikes, including this short bit on the motor, called “The Heart,” seen below.

Riding Impression

Our rides on the new Can-Am machines began in Valcourt, Canada, where the bikes were designed and the battery packs are produced. Final assembly is completed in Queretaro, Mexico. I started off on the street-focused Pulse (below) and put it in Eco mode, which would be a great way for a beginning rider to get started and is well-suited for riding around urban settings. But we were soon on the open roads outside of the small city, and I popped the Pulse into “Normal” mode for additional power. With a modicum of traffic on the two-lane byways, the Pulse had no trouble keeping with (and passing) traffic, and boasted solid acceleration and good road manners in terms of handling and decent comfort. It can make freeway speeds and beyond with little coaxing.

Soon enough, I swapped over to the Origin and was immediately rewarded with some additional leg room for my 34-inch inseam as well as a taller ride height. It felt very similar to the riding posture of my personal Suzuki DR650, just with no vibration and almost no sound from the drivetrain – and a fair bit more punch from the engine room.

On the road, the Origin has the same neutral ride manners as the Pulse, with a bit softer ride due to the longer-travel suspension. Sport Mode adds a bit more acceleration, and I also used the variable regenerative braking feature, but found that its range of control was too short in terms of throttle rotation. I’m used to using one-pedal driving mode in my electric car, and while not identical, the operational control is similar, and the Can-Am’s just need a few more degrees of rotation to be more controllable.

Eventually, we arrived at the motocross facility where the Can-Am team had set up a fairly sprawling off-road course to test the Origin’s dirt prowess. The track consisted of a fairly groomed forest-road type surface with substantial elevation changes, some loose dirt and sand in spots, tight turns, and a few rises that, with enough speed, riders could get the Origin in the air if so desired.

I set the Origin to Dirt Plus mode, which disabled the rear-wheel ABS and I also switched off traction control. Full motor power remained available, and as I circuited the course, I found it difficult to ride smoothly as the motor’s torque was almost overwhelming. Electric motors are all about torque, which is great on pavement, but with no gears and no clutch, the throttle and brakes were the only tools left to regulate the motor’s twist, and I was having a difficult time making the Origin do what I wanted on the low-traction surface. Having the rear brake ABS off and traction control off helped a bit, but the power delivery was still too abrupt. I pulled into the pits and talked with the Can-Am team about my experience, and we switched the bike to “regular” Dirt Mode, and I headed back out.

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

Photo by Can-Am/BRP

The change in modes calmed the power delivery significantly, and I felt much more in control of the Origin, so much so I even caught a bit of air off one of the rises, and the bike landed softly on the dirt track. Big fun! Too hot into a tight corner, I actually left the track into a small forested area, but was able to pick my way back through the trees to the track with no issue, the Origin displaying fine slow-speed controllability and balance at walking speeds – or slower. For tight, technical riding, Dirt Mode is where it’s at, to be sure, with Dirt Plus likely better suited for more wide-open spaces and higher speeds on more open (and straight) passages. Suspension compliance was quite good, with no bottoming and spot-on damping over rough bits, but I would like to have the option to add a bit of preload into the front fork.

From the dirt track, we got back on the small highways and headed back toward our base camp, curling around small lakes and through forested areas that reminded me of my riding routes around the Pacific Northwest – except all the signs were in French. And kilometers. Nous vous aimons, Canada.

Conclusions

It’s important to mention that we were riding pre-production examples of the new Can-Am Origin and Pulse, but they were essentially the same machines consumers will receive when the bikes go into production. Can-Am (and BRP) leadership were in attendance to get our feedback at a roundtable after our day-long riding session. My technical feedback was fairly straightforward: The left handlebar pod is overly busy with buttons. Massage that variable regen throttle movement a bit, and add front suspension adjustability (preload at least) if at all possible in a future iteration. Otherwise, I felt the bikes performed well, looked sharp, and were plenty capable – for what they are.

And “what they are” is electric motorcycles, a choice that struck me as odd when Can-Am’s legacy is race-winning gas-powered bikes, and I put the question to the powers that be at the roundtable: Why electric? Especially in light of the difficult market conditions for electric motorcycles, which are expensive and much more limited in range and refueling (charging) options than gassers – or electric cars and trucks. BRP and Can-Am leadership acknowledged these issues.

However, they countered by saying, essentially, that they are not a startup (BRP is a $5 billion USD company), and while the bikes have had a design progression, the internals – the battery, motor, and other bits – were already well-developed for their extensive line of electrified snowmobiles, which have had enthusiastic customer adoption. That aspect saved them a lot of time, effort, and money on the development side, and the electric tech will be more widely shared across other products as time goes on. Basically, they’re in it for the long haul on electric vehicles and not just motorcycles and snowmobiles. Sales may be slow now, initially, but as electrification becomes more mainstream – and the technologies continue to mature – Can-Am could be in a market leadership position on electric motorcycles in the fairly near future. It’s a gamble but likely a smart one, and as noted earlier, they already have plans in the works for more electric motorcycles (specifics were not shared, of course).

Also, BRP’s timing to market could be fortuitous. The new Can-Am bikes will tap into a growing trend of more urban-focused, middle-weight, and approachable beginner bikes, especially since they are electric. For non-enthusiast new riders, any motorcycle that looks cool, goes fast, is loaded with tech, doesn’t require learning to use a clutch and shifter, doesn’t require gas, and has extremely low maintenance requirements is going to be a compelling option. Even at the Origin and Pulse’s somewhat higher price point, the monthly cost to operate them will be low – and they will likely be eligible for substantial rebates/tax credits, which can ease the financial part of the deal. In time, if things go as planned, economies of scale may even bring down the price tag while improving performance – if the typical cycle of technological development holds true for electric vehicles, as it seems to be doing.

For us old-school moto jockeys, the Origin is not likely going to be our next choice for navigating a BDR or mounting a ’round-the-world expedition (but never say never). But for in-town riding and exploring the fringes of suburban boundaries, the Origin is an agile, comfortable, exhilarating machine from a brand long overdue for a rebirth.

For the nascent numbers of electric overlanders, tucking an Origin into the back of your van, electric pickup, or onto a trailer will allow for some quiet but capable exploration far off the pavement, with no gasoline required. Newer electric exploration platforms, like the Ford F-150 Lightning, Cybertruck, Rivian, and other upcoming EVs, will also be able to charge the Origin in the field since it uses a smallish battery pack. That’s a huge convenience – and allows for longer off-road rides from basecamp.

Can-Am may be celebrating its 50th birthday, but its focus is clearly on the future.

What to Know:

Can-Am Origin and Pulse Features:

- The Origin model comes with true off-road riding capabilities, and the Pulse model is configured for urban riding.

- Rotax-built liquid-cooled motor makes 47 horsepower, 53lb-ft/72Nm of torque and has reverse mode.

- The rider can adjust the regen level using the throttle.

- Widescreen 10.25-inch configurable touchscreen display with smartphone connection, app and CarPlay.

- Four riding modes on Pulse, Origin adds two off-road modes.

- 8.9kWh liquid-cooled battery is also a structural element with built-in Level 2 6.6kW charging capability.

- Chain drive and chain is sealed inside a casing to prolong service life.

- Pulse weighs 387 lbs (175.5 kg), Origin is 412 lbs (187 kg).

- Can-Am claims zero-60 mph time is 3.8 seconds.

- Off-road modes allow for turning off rear wheel ABS, decreasing front ABS sensitivity.

- Traction control can be turned off in several modes.

- “73” trim option adds a range of bits, special paint, and badges.

- Available accessories for Origin will include “LinQ” quick-mounts for panniers, windscreens, racks, and more.

- Prices for Origin will start at $14,499, and Pulse will start at $13,999.

- Two-year overall warranty, five years on battery.